Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

The Rise and Fall of the Early 20th Century Scottish 'Monochromists'

By Graham Fitzpatrick, 30.11.2021

The current market for British prints is buoyant, with the colourful, avant-garde screenprints and lithographs of the mid 20th century particularly popular. Good examples were to be found at Bonhams' recent Prints and Multiples sale. David Hockney led the way with one of his lithographs fetching £19,625 (including premium). Less popular and hence more affordable, is the black and white realism of early 20th century etching and drypoint printmaking. Today, only recognised masterpieces of the genre, where prices still manage to make four-figure sums, would stand a chance of making a major London sale. In over 300 lots in the Prints and Multiples Bonhams' sale, only two such pieces were on offer; an Augustus John self portrait and an early Graham Sutherland pastoral scene. The majority turn up in smaller auction houses with prices in the low to mid £100s range. This is in stark contrast to the prices they commanded in their heyday, when the best examples could fetch the then average price of a house.

As prices for monochrome prints soared during the early 20th century, collectors were both captivated by the quality of the prints and their attractive potential as investment opportunities. Artists benefited from the high prices, but buyers found that they too had the opportunity to make money by reselling them at even higher prices, often not long after buying them. There is evidence to suggest that some artists were willing to exploit this craze for prints by modifying their original plates and reissuing them as different states, maximising their income from one image. Whatever their motivation, there is no doubt that some of the best artists of the day were attracted into this booming market, explaining the high quality of many of these prints. But despite this, they are now largely overlooked. Three of the very best of monochrome printmakers were Scots.

Sir David Young Cameron, The Five Sisters, York Minster, 1907. Private Collection on long term loan to the National Galleries of Scotland.

Sir David Young Cameron, The Five Sisters, York Minster, 1907. Private Collection on long term loan to the National Galleries of Scotland.

David Young Cameron (1865-1945)

Cameron's prints of church interiors attracted particular attention on the art market; an etching of Five Sisters, York Minster (1907) famously sold for £660 in 1928, this would be over £40,000 in today’s money. Another copy sold in America for less than £2,000 in 2005, reflecting their current fall from grace.

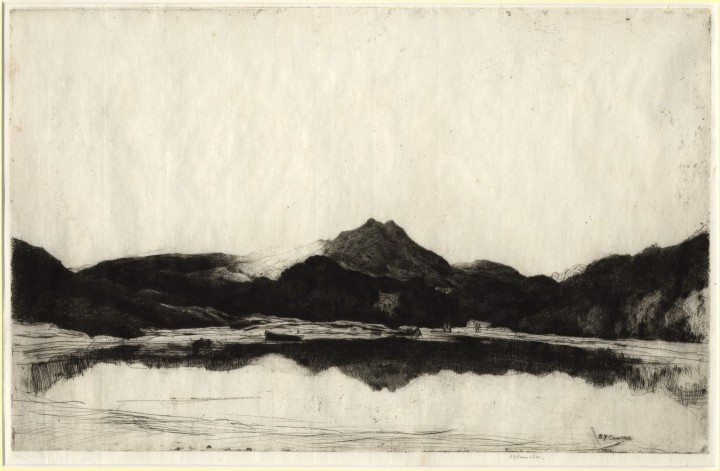

In 1923, following extensive travels around Europe and a 6-year break from etching (thought to be the result of his disapproval of the more cynical activities concerning print production on the art market) Cameron produced two of his finest prints; Ben Lomond and Thermae of Caracalla. Whilst his earlier architectural work focused on quality of line, these later pieces display a textural richness and depth of emotion. This shift in style coincided with his increased use of drypoint, a medium that lends itself to this effect. Time spent in France, where Impressionism was still prevalent, may also have been a factor.

Muirhead Bone, Rainy Night in Rome, 1913. Courtesy of Campbell Fine Art.

Muirhead Bone, Rainy Night in Rome, 1913. Courtesy of Campbell Fine Art.

Muirhead Bone (1876-1953)

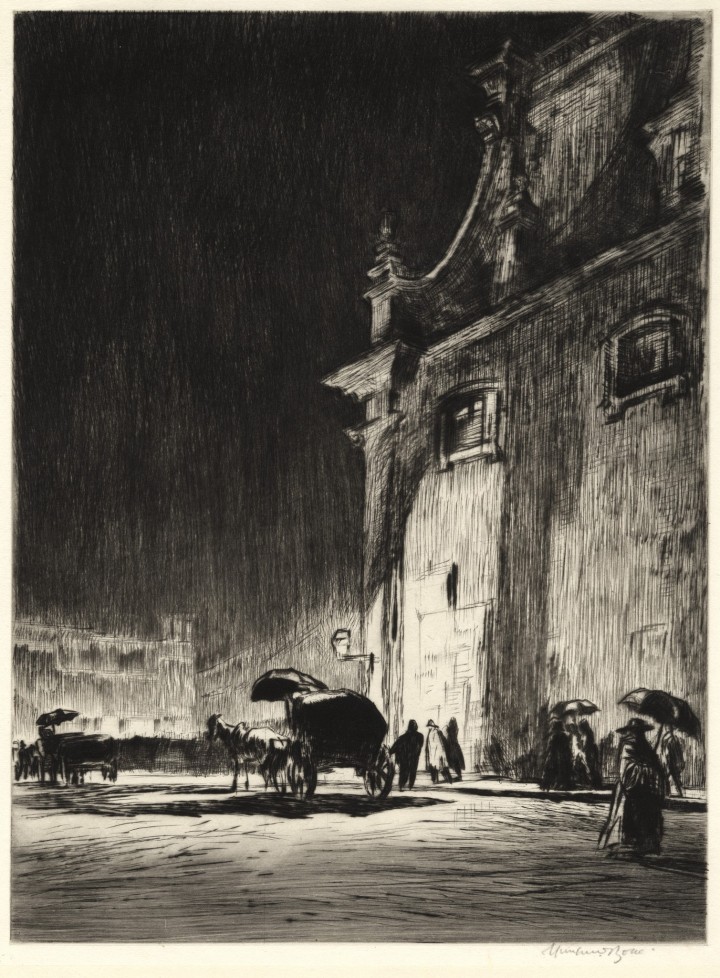

Whilst training to be an architect, Bone attended evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art. His natural talent as a draughtsman and interest in architecture is reflected in superb early drypoints, such as Rainy Night in Rome (1913), a print of which is currently available to purchase through the London Original Print Fair for £1600.

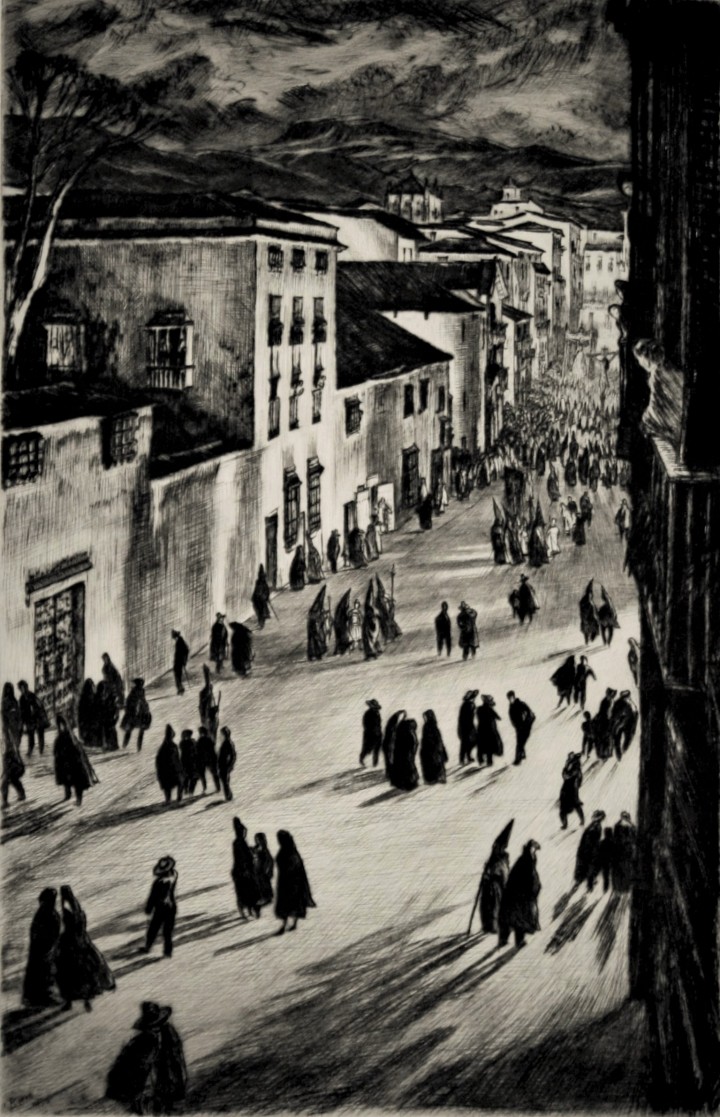

One of Bone's most acclaimed prints, A Spanish Good Friday (1925) shows a crowd celebrating Holy Week; its eerie mood made possible by the incredible ink retention. It is a good example of the trend amongst artists to produce multiple versions of the same image, in this case, a record 29 states. A catalogue at the time priced a version of the print at a staggering £500; which is the equivalent of £30,000 in today's money. Another version is currently available to buy through the Allinson Gallery for $500.

Muirhead Bone, A Spanish Good Friday, 1925. Courtesy of the Allinson Gallery.

Muirhead Bone, A Spanish Good Friday, 1925. Courtesy of the Allinson Gallery.

James McBey (1883-1959)

Aberdeen born, McBey was brought up in poverty by his mother. He briefly attended the local Gray’s School of Art, although he was largely self taught, having to use the family mangle for printing. His early circumstances forced him to spend over a decade working in a local bank, during which he managed to save £200 which financed a trip to Holland in 1910. Seeing Rembrandt prints first hand, he was inspired to produce a series of 21 plates, which included acclaimed works such as Amsterdam from Ransdorp, Zaandijk and Omval. The commercial success of these works enabled a trip to Spain, following a brief spell in London.

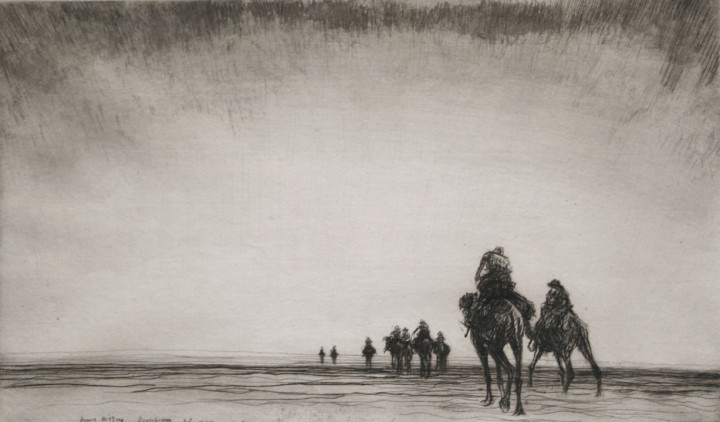

By now McBey was developing a strong reputation and a sell-out sale followed at the Goupil Gallery in London. During WW1 McBey was appointed the official war artist to the Palestine Expeditionary Force and on his return he used his drawings to produce a series of etchings. An impression of McBey’s wartime print, Dawn, The Camel Patrol Setting Out, realised £445 at auction in 1928, the highest price ever attained for a living etcher’s work in the UK. In today’s money this would be approaching £30k. A version of another of McBey's most renowned war time prints, Strange Signals (1919) was valued between £150-£200 in a 2005 Bonhams sale.

James McBey, Dawn, The Camel Patrol Setting Out, 1919.

James McBey, Dawn, The Camel Patrol Setting Out, 1919.

The Vagaries of the Art Market

The printmaking boom began to decline in the 1920s and the Wall Street Crash in 1929 brought the bubble to an end. Like most of their contemporaries, Cameron, Bone and McBey ceased etching by the early 1930s. Their contemporaries, the Scottish Colourists could only dream of the sort of success they were enjoying at the beginning of the 20th century. Since being recognised in their own right as some of the first British Modernists, it is now the Colourists’ turn to be fetching the huge prices that place them out of reach for most, regularly achieving six-figure sums at auction.

If you’re attracted by the idea of owning some early 20th Century Scottish art, the sheer quality of the Scottish Monochromists draughtsmanship and their ability to create intense, atmospheric and emotive images, make them worthy of your attention. Who knows, one day they might regain their previous popularity.

James McBey, Strange Signals, 1919. Private Collection on long term loan to the National Galleries of Scotland.

James McBey, Strange Signals, 1919. Private Collection on long term loan to the National Galleries of Scotland.

Graham Fitzpatrick is an Economist, art collector and contributor to Antique Collecting