Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Text Disabled

By Greg Thomas, 17.11.2021

Acts of Observation, a group exhibition at Collective, Edinburgh, explores the linguistic and systemic traps that assail disabled people, but also works around them to propose new ways of representing bodies and lives. Greg Thomas negotiates.

The so-called social model of disability is now de rigueur across much public, private, and third-sector discourse in the Anglophone west and beyond. At its heart is a simple and enticing proposal: that people are disabled by the barriers that society puts in their way rather than the inherent capacities of their bodies (including their minds). An example often cited involves a wheelchair user and a set of steps leading up to a public building. It’s not the need for the wheelchair that disables, but the unthinking design of that public space in a way that impedes further movement.

The social model is undoubtedly a humanising force—which is not to say that it has been widely realised in practice. But the sleight of hand by which all disability is reduced in public imagination to wheelchair use is symptomatic of a wider tendency towards reductive thinking on the matter. Not all disability involves visible physical difference, nor do most of the barriers disabled people face concern their literal movement through space. The byzantine and punitive maze of Personal Independence Payment assessment or a Universal Credit application, for example, represents a greater threat to the dignity of disabled life in the UK today than Victorian civic infrastructure.

Ana García JácomeIt, Like She Had Never Existed, video still, 2018.

Ana García JácomeIt, Like She Had Never Existed, video still, 2018.

Acts of Observation brings together four artists, Ana García Jácome, Abi Palmer, Jeda Pearl & Simon Yuill, variously concerned with the institutional and symbolic systems that channel and constrain disabled experience; but they also use language and symbol in the service of hopeful imagination. The most moving work on display is García Jácome’s film It’s Like She Had Never Existed, playing in the City Observatory, which depicts the life of Coquis, Ana’s aunt in her home country of Mexico. A mixture of archival footage and animation frames a family member’s reminiscences of Coquis’s life, from a childhood in which she was recognised with concern as 'not normal' – 'she kept punching herself' – to harrowing accounts of adult confinement in a psychiatric hospital. The warmth and geniality of the male voice-over expresses sympathy rather than empathy, the tone of the film as a whole subtly emphasising the point that without social structures and language that humanise disabled people, the love and attention of family is often not enough.

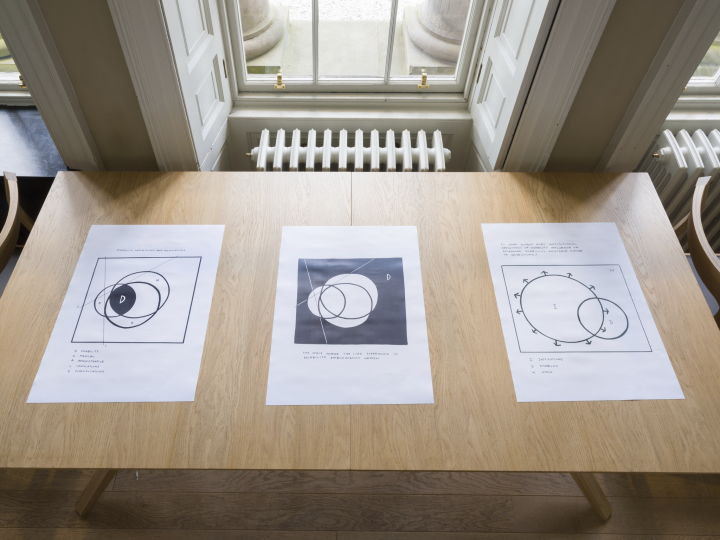

A second film by García Jácome explores the history of institutional conceptions of disability in Mexico, and looks to potential futures. The artist calls for lithe and multi-symbolic evocations of what disability can and does mean, alive to (neuro)divergent modes of such as 'sign language and abstract code,' and incorporating physical and embodied ways of knowing. A set of posters showing comic pseudo-graphs that attempt, with tongue in cheek, to draw distinctions between institutional and lived articulations of disability offset the point, while gesturing in earnest towards such alternative grammars and lexicons of expression.

Simon Yuill, Recovery Time is Labour Time, painted pillar, part of Acts of Observation, Collective, 2021. Photo by Tom Nolan.

Simon Yuill, Recovery Time is Labour Time, painted pillar, part of Acts of Observation, Collective, 2021. Photo by Tom Nolan.

In the next room, Yuill’s majestic circular column text 'Recovery Time is Labour Time' loops endlessly around itself, drawing attention to the emotional and physical stakes of negotiating employment services and work while living with ongoing fatigue. It is a smart and beautiful piece with one foot in the concrete poetic tradition of Scottish literature, drawing attention to the spiral of psychosomatic effects that can push disabled people to the fringes of economies and labour markets. Accompanying it is a fold-out manifesto-poster on the concept of 'stimming,' the sensory pattern-making that autistic people use for emotional regulation, recovery, and interaction. Yuill’s thoughts here dovetail effectively with García Jácome’s calls for openness to more expansive means of articulating disabled identity.

So too, Jeda Pearl’s poems, played through speakers on the viewing terrace and also made available as a free pamphlet, envisage a future state of multisensory agency for disabled people, which also comprises a kind of space-age utopia:

Your dancing walk crests majestic rainbows.

You are resplendent in wheels, walker, or cane

Resident deejays turntable larynx devotions –

Makes your breakbeat st-stuttering float

Your disabled body holds sacred geometries

Sing this affirmation!

My disabled body holds sacred geometries

(“Sublime Body Reveals Itself”)

En route to the heights of this vision, however, Pearl explores the doldrums of chronic pain, imagining in 'Empathy Remedy' how she might 'brew an elixir of empathy' for the non-disabled: 'I’d have to fill/ it with spelks of rough-cut crystal/ rattle glass down-arm to your fingertips/ lodge them in your fingers and toes.'

.png) Abi Palmer, Crip Casino, 2018.

Abi Palmer, Crip Casino, 2018.

Over in the City Dome, Abi Palmer’s Crip Casino rounds things off with its surreal, interactive satire on benefits application and medical treatment processes. Visitors are invited to play with a set of doctored Elvis-themed fruit machines to generate absurd, chance-based medical descriptors and diagnoses: 'twist/ your left armpit/ with grace/ daily,' 'shake/ a rumour you wept last Friday/ until you fall down crying/ seven times.' Across the room is a gaudy tin-foiled and toy-covered National Health Shrine, draped in fairy lights and accompanied by a film-work: Assessment Booth Three, in which an assessor and interlocutor using a paper fortune-teller inscribed with arcane graphic symbols – alongside a set of bizarrely probing questions about dreams and religious faith – to determine the applicant’s right to take treats from the altar. A deific embodiment of the Shrine, however, warns us not to 'game the system.'

Taken as a whole, these pieces explore the invisible, discursive and institutional barriers that deny people agency: language disables throughout. What is striking, however, given the ongoing ideological war waged on disabled agency and dignity by UK government policy, is the note of defiant hope that is struck throughout the show, which turns language, in the widest possible sense, into a tool of liberation.

Acts of Observation is showing at Collective until 2nd January.