Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Press Release - This Fragile Earth: How pioneer Scottish Artists anticipated the climate crisis

02.03.2023

Press Release 02.03.23

A ground-breaking exhibition by the Fleming Collection of Scottish art, staged in Coventry Cathedral, focusses on a group of veteran artists who were ahead of their time in responding to the threat of climate change.

Until now, these artists, although known to one another, have never been perceived as a group with common artistic goals. It was the gifting to the collection in 2022 of James Morrison’s monumental (6 metres in length) Arctic Mural (1995) that led director of the Fleming Collection, James Knox, to investigate whether other Scottish-based artists shared similar preoccupations around that time or earlier; and if so, why?

His search led him to examine the work and careers of six artists. They are painters Frances Walker (born 1930), James Morrison (1932-2020) and Glen Onwin (born 1947); visual artist and constructivist, Will MacLean (born 1941); artist / filmmaker Elizabeth Ogilvie (born 1946); and expeditionary artist and photographer Thomas Joshua Cooper (born 1946). Onwin and Ogilvie are also noted producers and designers of multi-disciplinary installations, often of staggering scale and ambition.

Despite their varying disciplines, what are the threads that bind them? First, a common instinct, driven by geography, to engage with the topography and ecology of the North, which they see as stretching from Scotland’s north-western coastland and archipelago to Greenland, to Canada’s High Arctic – and in Cooper’s case to the North Pole itself. This placed them at the frontiers of climate change where the onset of global warming was most immediately felt. Take Walker’s 1987 landscape, After the Storm of the Inner Hebridean island of Tiree, painted at a time when she was voicing concerns about “the sea level rising …and engulfing most of low-lying Tiree like another Atlantis.”

Will Maclean, Red Ley Marker, (1989) . Mixed media on board . The Fleming Collection Ⓒ Will Maclean MBE RSA

Will Maclean, Red Ley Marker, (1989) . Mixed media on board . The Fleming Collection Ⓒ Will Maclean MBE RSA

History also plays its part. Maclean’s forebears were victims of the Highland Clearances when his great grandfather was forced off the land to join the herring fleet. Two generation later this occupation also collapsed due to modernisation. Much of Maclean’s work – both as a graphic artist and maker of assemblages of found and carved objects - mourns the loss of age-old working communities and memorialises their links to archaic pasts. Ogilvie’s family had to leave the remote island of St Kilda in 1930, along with the rest of the population, triggering her life-long interest in lives lived on the edge of existence and to a related preoccupation with the sea from early drawings of ‘wave-scapes’ to her recent film of kelp forests, projected onto the Cop 26 venue in Glasgow. Walker, always drawn to the wild and desolate spaces feels a similar kinship with St Kilda. A further shared sense of loss is that of the Gaelic language.

Beyond Scotland, Morrison worked alongside a community of Inuit peoples in the Canadian High Arctic who had been forcibly re-settled from their traditional territories by the Canadian government. For Morrison, their fortitude in the face of injustice heighted the emotional intensity of his Arctic paintings, which, devoid of people, depicted a colossal landscape sublimely indifferent to mankind. Equally, Cooper, who is of Cherokee descent, spent formative years as a boy on an American Indian reservation which led to his understanding of the trauma of his ancestors and by association ‘cleared’ Highlanders ‘being moved from their own sense of belonging.’

These artists’ backgrounds and experiences led them to engage with the consequences of brutal social disruption and spiritual exile long before the effects of climate change had impacted upon the communities of the Arctic Circle and in other precarious environments around the globe. Following his expeditions to the High Arctic James Morrison was left in no doubt as to what the future held: “We are hell bent on destroying the planet.” He said in 1997. “I simply do not see homo sapiens making the decisions, the self-sacrificing decisions, to save the planet. I think the planet will run on to oblivion.”

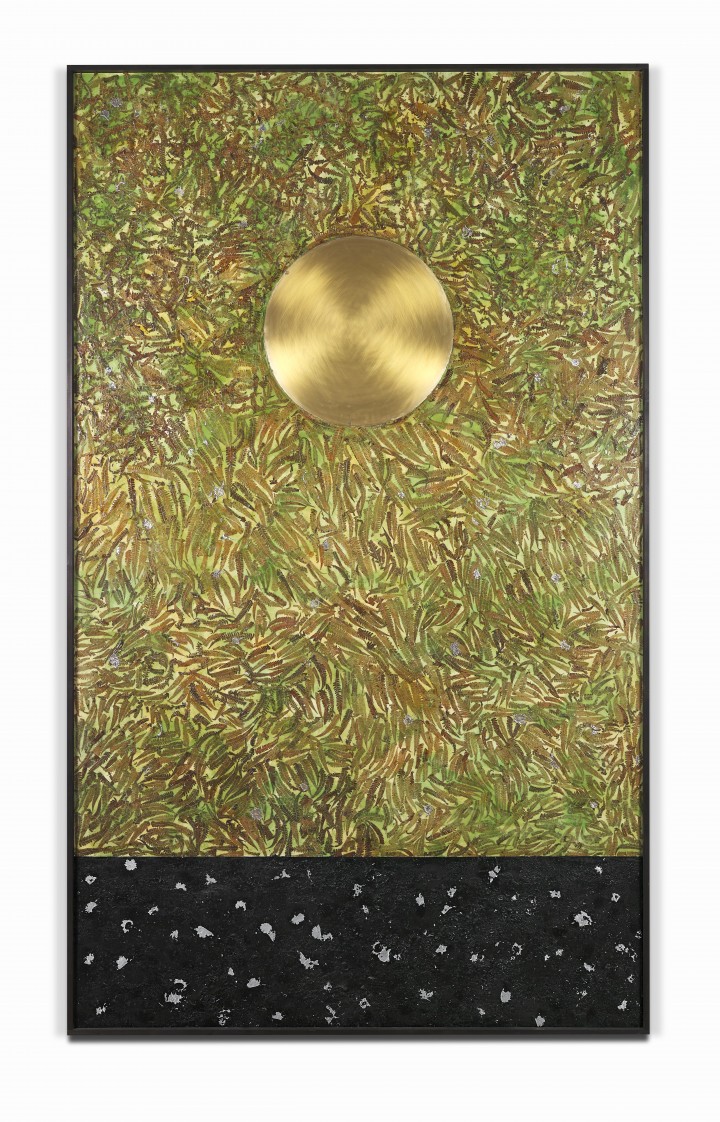

Glen Own, Photosynthesis, Open the Kingdom, (1987). Organic matter, coal, metal, oil, wax and shellac on canvas mounted on board. The Fleming Collection © The Artist.

Glen Own, Photosynthesis, Open the Kingdom, (1987). Organic matter, coal, metal, oil, wax and shellac on canvas mounted on board. The Fleming Collection © The Artist.

Onwin differs from the others in that his development as an environmental artist sprang not from looking north, but from exploring the environs close to his native Edinburgh. His discovery of a coastal salt marsh in East Lothian with its cycles of growth and degradation led not just to a major land art project in the early 1970s but to a life-long career of visualising the earth’s history and ecology. His 1988 exhibition Revenges of Nature featured monumental paintings that sounded the tocsin on man’s destruction of the planet. One of the key works from the cycle, representing the source of life on earth, Photosynthesis made from ferns, coal dust and other materials, is in the exhibition.

Collectively, these six artists are not well known to a wide public outside Scotland. And yet they deserve to be. Their prescient response, stretching back forty years or more, to the now full-blown climate crisis, has always been part of themselves and their art resulting in works of intense feeling, meaning and beauty. At a time when the climate crisis has rightly become a central preoccupation for artists across the globe, now is the time to acknowledge those who forged the way.

James Knox, Director of the Fleming Collection says, “This landmark show installed in the modernist masterpiece, Coventry Cathedral, which incidentally was designed by a Scot, will open the eyes of the public to the sensibility of Scottish artists to the threats and consequences of climate change as expressed through works of great beauty and force.”

The Very Revd John Witcombe MA MPhil, Dean of Coventry says “We are delighted to be welcoming this important exhibition of works from the Fleming Collection to Coventry Cathedral. It will bring a fresh perspective on reconciliation with the earth into the heart of Coventry, casting our eyes and hearts north to the view of the planet from above, and challenging us through both beauty and peril – as artic exploration has always done - to discover our own response in this time of climate crisis.”

NOTES FOR EDITORS

A WIDE SELECTION OF HIGH RESOLUTION IMAGES FOR MEDIA USE CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE

The Artists:

Thomas Joshua Cooper (b.1946 San Francisco)

Growing up on an American Indian reservation Cooper was taught ‘how to live honourably in the natural world and not to do purposeful damage.’ Having studied photography at the University of New Mexico, he pursued a parallel career as teacher and artist, establishing in 1982 the Fine Art Photography programme at Glasgow School of Art. Describing himself as an expeditionary artist, he works on long term projects which take him to the world’s extremities working only with a 1895 American field camera, requiring single frames, long exposures and hand processing. He almost died at the North Pole falling through the ice. Having hauled himself out, he realised: ‘I’m at the actual top of the world. I can do this. The weather was perfect with the freezing fog that rose.’

James Morrison (1932-2020)

Born in Glasgow, trained at Glasgow School of Art, Morrison moved to the remote north-eastern fishing village of Catterline in the 1950s, where he worked closely with his friend Joan Eardley, an influence on his burgeoning interest in landscape painting. His first expedition in 1990 to Ellesmere Island in Canada’s High Arctic was at the suggestion of Scottish botanist Dr Jean Balfour. Initially working on a small scale, he returned twice more to different locations transporting large boards, which freed him to capture the illusionistic space of the landscape. The Arctic Mural was inspired by his 1994 visit to Grise Fiord the northernmost civilian settlement in Canada. Commissioned for an exhibition at Edinburgh University’s Talbot Rice Gallery, it was, given its scale, largely painted in situ in the run up to the opening. For Morrison, who went on to become one of Scotland’s most renowned landscape painters, his Arctic landscapes were the defining moment in his career.

Will Maclean (b.1941 Inverness)

Born into a line of seafarers, Maclean at fifteen trained for the merchant navy spending two years at sea. Poor eyesight forced him to change tack, leading him to develop his artistic talent at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen where he was taught by Frances Walker. His first mature work, the 1978 Ring Net project, was a documentary exhibition on herring fishing off Skye consisting of photographs, drawings and found objects. His practice developed as a maker of assemblages and boxed constructions of found, carved and painted objects. Themes extend to archaic and magical symbolism, evoking seers, shamans and bards; to early navigators of the high latitudes such as Celtic monks, whalers and early polar explorers; and to those dispossessed by the Highland clearances. He has also worked collaboratively on five large scale stone built ‘megalithic monuments’ on the Isle of Lewis

Elizabeth Ogilvie (b. 1946 Montrose)

Growing up as an only child in the Highlands, Ogilvie’s earliest memories are playing in the waters of the River North Esk. Her lifelong preoccupation with water as a material for her art was born. Equally her need to ‘head north and run wild’ sprang from her mother’s roots in the north Atlantic Island of St Kilda, which Ogilvie visited on numerous occasions saying ‘it was coming home’. A traditional training in life drawing at Edinburgh College of Art informed a series of beautiful early ‘wave drawings’ often displayed as part of installations. The latter, which developed from collaborative projects with like-minded artist Robert Callender, led to later solo installations in public galleries involving film, music, dance and engineering. Her latest film Into the Oceanic made with Rob Page, highlights the power of kelp forests to sequester carbon.

Glen Onwin (b. 1947 Edinburgh)

Although trained as a painter at Edinburgh Collection of Art, Onwin’s 1975 Saltmarsh project was one of the earliest examples of land art in the UK, directly inspired by Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in Great Salt Lake. Onwin has always connected to currents in the international contemporary art world and acknowledges his debt to the Italian Arte Povera movement in his use of a variety of materials such as marsh mud, flora and coal dust to make his work. Following his 1988 Revenges of Nature exhibition, Onwin staged monumental installations on ecological themes in Lincoln Cathedral and in a semi-derelict Methodist chapel in Halifax as well as in public galleries such as the Arnolfini. His latest works are abstract paintings such as Twofold Trinity (in the exhibition) made from sulphur, carbon and coal dust collected from a decommissioned power station outside Edinburgh.

Frances Walker (b.1930 Kirkcaldy)

Trained at Edinburgh College of Art, Walker went on to become the sole art teacher for all the schools in the Outer Hebridean Islands of Harris and North Uist, which reinforced her love of wild and desolate spaces and her desire to depict isolated panoramas and landscapes. As an artist, Walker is renowned in Scotland for her paintings and etchings of remote places, which has also taken her to Greenland and the Antarctic. From 1971 she also lived part of the year on the island of Tiree, which she described as ‘on the fringe of Europe - a place of great glittering beaches with the wide sky, the clouds, the seabirds in flight..’ before issuing her dire warning in 1989 on the threats of rising sea levels and oil pollution to the island. Now in her 93rd year, Walker lives in Aberdeen.

About the Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation

The Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation owes its existence to the formation of the finest collection of Scottish art outside public institutions, comprising over 600 works from the 17th-century to the present day. The Fleming Collection dates back to 1968 when investment bank Robert Fleming & Co, began to acquire Scottish art to hang in its offices worldwide to reflect its Dundonian roots. Following the sale of the bank in 2000, the Collection was vested in the Foundation. Today, the Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation is endowed to care and enhance the Collection and to promote an understanding and awareness of Scottish art and creativity across the UK and beyond through a programme of cultural diplomacy, touring exhibitions, individual loans, events, publishing and education. www.flemingcollection.com

A Note on Being Scottish

The Fleming Collection’s definition of a Scottish artist is anyone born in Scotland, trained in Scotland or who has lived in Scotland for a long period or been part of a significant Scottish art movement. Five of the artists in this exhibition have lived in Scotland all their lives. Thomas Joshua Cooper was born in America, but has lived and worked in Scotland since 1982 when he set up the Fine Art Photography course at Glasgow School of Art.

About Coventry Cathedral

Designed by modernist Scottish architect, Sir Basil Spence, the ‘new’ Coventry Cathedral, which was consecrated in 1962, adjoins the ruins of the medieval cathedral destroyed in a bombing raid in 1940. The cathedral, which was enriched with contemporary art commissioned for the building, is considered one of the UK’s greatest twentieth century buildings. The cathedral’s history focusses on the complex and often conflicting relationship between man and nature. This Fragile Earth fits naturally into the context of Coventry Cathedral, which is a centre of reconciliation, highlighting the diversity of its mission and testifying to its present-day importance. As the city itself, much of the Cathedral was destroyed during the Coventry Blitz which was said to be one of the worst raids of the Second World War, changing the face of the city – with its impact still felt today. Coventry Cathedral is one of the world’s oldest religious-based centres for reconciliation, and its work in recent decades has involved it in some of the world’s most difficult and long-standing areas of conflict. Still today the medieval ruins continue to remind us of our human capacity both to destroy and to reach out to our enemies in friendship and reconciliation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, INTERVIEWS AND IMAGES

Tracy Jones, Brera PR – tracy@brera-london.com / 01702 216658 / 07887 514984 / www.brera-london.com

This Fragile Earth: How pioneer Scottish Artists anticipated the climate crisis is exhibited at Coventry Cathedral, 4 April - 29 May 2023