Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Of Books, Barns, and Boats

By Greg Thomas, 25.02.2022

Leonard McDermid’s Stichill Marigold Press uses traditional letterpress techniques to create lyrical assemblages of word and image exploring rural and nautical themes. Greg Thomas reviews a show curated in his honour at the Scottish Poetry Library.

A note accompanying the works by and about Leonard McDermid currently on display at the Scottish Poetry Library states that the poet and publisher has “enjoyed over seventy years of looking at things, and over fifty years of commenting on them.” As the tone of this remark might suggest, the aims of McDermid’s Stichill Marigold Press, founded during the 1990s, are avowedly modest: “to provoke smiles or quiet pondering,” as a 2019 exhibition note has it. This is a task accomplished through the production of exquisite miniature booklets, pamphlets, cards, paintings, and occasional three-dimensional artworks taking the form of the book – or other domestic detritus – as their basis.

Fair Winds and Following Seas, as curator Barbara Morton notes, primarily showcases a collection of works presented as a personal gift to McDermid and his wife Jean, created by various friends of the press: Jane Hyslop, Graeme Hawley, Julie Johnstone, John Easson, Thomas A Clark, Catherine Marshall, W J Morton, Barbara A Morton, Susie Wilson, Imi Maufe, and Gin Saunders. The collected works were initially exhibited at the Edinburgh College of Art Library in Autumn 2021, from which followed an opportunity to exhibit at the Scottish Poetry Library. Because of the greater available space at the library, Morton asked McDermid to show some of his own works, with two aims in mind: firstly, to bring the work of Stichill Marigold to light collectively, and secondly, to present to an audience the remarkable synergy that occurred by way of artistic response.

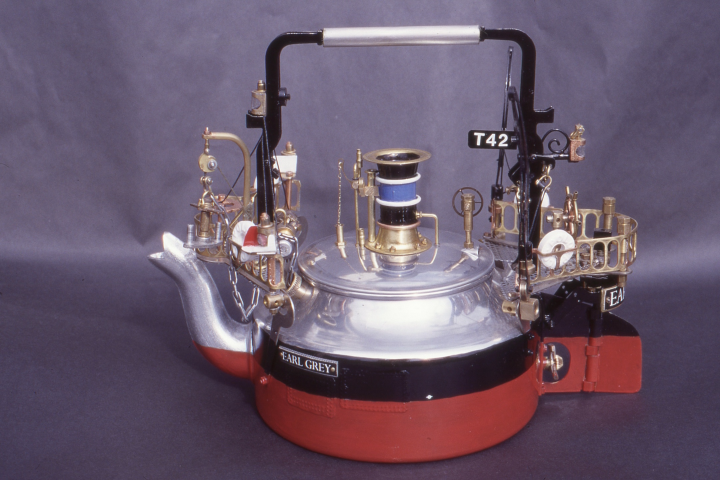

Leonard McDermid, Hot Water Tender T42, 1999.

Leonard McDermid, Hot Water Tender T42, 1999.

Amongst the most captivating pieces of McDermid’s on display at the library until 26 March are works resting on old hardback books used as plinths or pedestals. A little plywood farm-building is impressed with the phrase “Tithe Barn” (the other, invisible side reads “Harvest Home” in golden yellow print). An upturned steamer sinks into a blue fabric sea (the front cover of a copy of Henry Newbolt’s 1925 text The Tide of Time). Its deck, funnel, and hull are embossed with gnomic phrases about to be carried down to Davey Jones’s Locker. Then there is the marvellous Hot Water Tender T42, an old aluminium kettle decked out with winches, rails, a life-ring and ship’s wheel.

The label accompanying the latter piece brews up a fanciful history in which the stove-top vessel was one of a fleet during 1880-1914, that “operated out of Falmouth, seeking inward bound-tea-clippers. On sighting a sail, the tender would be rapidly brought to the boil and made fast alongside. Without any loss of speed, the cargo was sampled, and the results semaphored to shore signal stations for onward relay to London.” Visual and sculptural symbols are often coaxed into a state of comic or lyrical clarity by annotative notes or poems like these. While the exhibition suffers from the perennial problem of displaying books in vitrines when ideally they would be available for tactile encounter, the library shop offers a bounty of printed matter in which this visual-literary equilibrium is beautifully mustered.

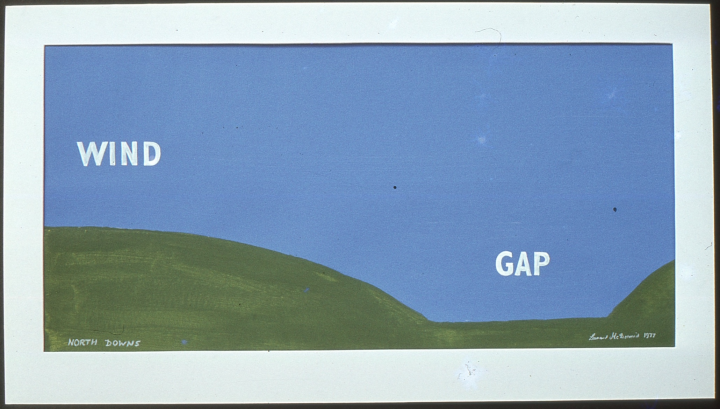

Leonard McDermid, Wind Gap.

Leonard McDermid, Wind Gap.

The naivete of McDermid’s idiom, also clear from the above vignette, is studied but never faked. Indeed, its artistic lineage a disarmingly rich one, with the products of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn Press an enlightening point of reference. The mite of sentiment that captures the spirit in both artists’ work is secured in McDermid’s case by a rustic compendium of themes similar to that of his sometime peer: seas and rivers, boats and tugs, cornfields and valleys, coal-powered trains, tickets and dockets for the voyage. But the martial toughness and trenchant intellection of Finlay’s practice is not in evidence. Without wanting to sink the Marigold under weight of comparison, might Finlay’s printed oeuvre have come to resemble something like this generous and ludic assortment had he not been so consumed (admittedly productively) by cultural battles and the ghosts of history?

It’s also worth noting the place Stichill Marigold assumes, in poetic terms, in a loosely post-objectivist tradition of minimal nature writing: spartan, speech-paced verse containing traces of folk doggerel and regional demotic. In the 1960s this approach united a group of poets and artists spread between Britain – particularly Scotland – and North America, dubbed “avant-folk” by the critic Ross Hair. Contemporary poets alert to this lineage include Thomas A Clark, amongst the many talented friends and peers to respond to McDermid’s work with cards, booklets, or miniature sculptures of their own. All of the pieces presented in homage offer fitting tribute to McDermid’s endeavour. Indeed, this is a cohesive and transportive collective show, one to lift the spirits and delight the senses.

Fair Winds and Following Seas is exhibited at the Scottish Poetry Library until 26th March.