Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Isolation in Scottish Art: Craigie Aitchison

By Susan Mansfield, 01.06.2020

There is something very confusing about simplicity. We are used to art which presents us with multi-layered problems to solve. Art which does not is apt to confound us. The paintings of Craigie Aitchison - saturated in colour, distilled in form - leave us unsure how to talk about them.

Aitchison died in 2009 after a painting career lasting more than 50 years in which he calmly ignored the fluctuations of fashion. Throughout his life, he returned to the same subjects: crucifixions, still lifes, animals, landscapes. He resisted being asked about his work because he said it made his pictures “more complicated than I could ever have intended them to be.” His friend, the artist Graham Snow, said, in an interview with The Scotsman in 2012: “His paintings look very charming and colourful and easy, but he disliked people saying his work was primitive or naive. It’s not, it’s simple, and he would say that’s the hardest thing to do.”

An Aitchison painting is a unifying act of form and colour. He isolates a subject against a richly coloured background - the crucified Christ, a bedlington terrier, a vase with a single flower. It’s a supreme act of focus, eliminating all non-essentials. Yet those background colours - hot pink, emerald, midnight blue - become much more than a background. Each part of the painting is in relationship with all the others.

For him, this was an undertaking of utmost seriousness. In 1969, the normally mild-tempered Aitchison issued a writ against a London magazine which used a painting of his on its cover because the proportions had been altered and the painting overprinted. Simplicity has exacting requirements. There is no room to get anything wrong.

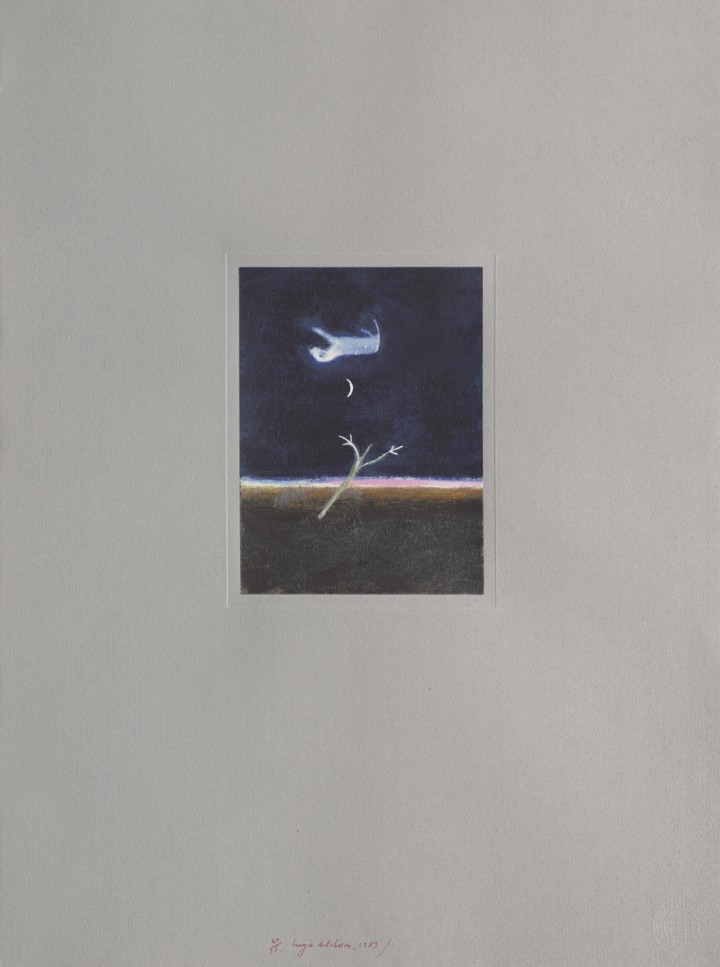

Craigie Aitchison, Wayne Going to Heaven, 1989. © The Artist's Estate. All Rights Reserved 2019/Bridgeman Images

Craigie Aitchison, Wayne Going to Heaven, 1989. © The Artist's Estate. All Rights Reserved 2019/Bridgeman Images

While the abstract qualities of shape and colour are immensely important, these are not abstract works. Nor are they works of symbolism. The things in these pictures are the things themselves. Aitchison doesn’t just paint a dog, he paints a bedlington terrier, because these were his dogs and he loved them. He once said of the crucifixion: “It is a horrific story, and more worth trying to say something about than anything else that’s happened since.”

But neither are they life-like representations. Throughout his life, Aitchison was drawn to the work of the Italian early moderns such as Giotto and Piero della Francesca. Like them, he paints a scene in its essence, he manipulates the space on the picture plane. He also paints feelings, explore his relationship to the things he paints. In this he is capable of great pathos, from the yellow bird perched on a three-branched tree to the small, vulnerable Christ figure, alone but for a single faithful bedlington terrier at the foot of the cross.

Matisse also admired Giotto. In 2010, the art critic Bill Hare fruitfully explored the similarities between Aitchison and Matisse (both northerners who fell in love with the south, both lawyers who gave up law for art). If the challenge facing modern art is to deal with the modern world - its pace, its technology, it’s endless sensation - one way to do that is to resolve this barrage of stimulation by focus and distillation. This is what Mattise was about; in an interview in 1909 he said: “We work toward serenity through simplification of ideas and form.” A lot might be gained from seeing Aitchison in this light.

But he was doing this in London in the 1950s, in an art world coloured not by Matisse but by Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, Frank Auerbach. He chose his own, singular path, the path of simplicity. Perhaps, as he said himself, the most difficult thing of all.