Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Empty Abundant Gardens

By Greg Thomas, 22.11.2022

The brightly patterned carpets of Glasgow’s Mitchell Library flow like a psychedelic sea from Department to Department, intersecting spaces dedicated to the neat division of knowledge into schools and discourses. You might read them as a freewheeling counterpoint to that aspect of human thought wedded to taxonomy and genealogy. But there is also an underlying and hypnotic order in the repeat-patterning of the designs, dependent, as Elizabeth Price notes in the press release attached to her current show at Glasgow’s Hunterian, on Jacquard loom technologies. Still utilised by mass carpet manufacturers, the Jacquard loom originally used punch cards to generate complex weft patterns. The system was influential on the early development of computing as a means of processing large quantities of data immune to human error through binary code.

There is a thread of connections implied here – between the neatness of institutional memory and its oversights within collective history and identity, dichotomies between rational and creative expression that resolve into deeper congruences, the analogue and the digital – that have sustained Price’s practice in moving image over several decades. Film-work UNDERFOOT, the centre-piece of the show, is based on her research with the records of two world-famous carpet-manufacturers based in Renfrewshire and Glasgow, Stoddard International Plc and James Templeton & Co, as well as her explorations of the Mitchell. Ltd. ‘SAD CARREL’, the other work on display, is a delightful hand-tufted rug stretched around the inside of a concave screen. Created in collaboration with Dovecot studios, the design extrapolates from a vinyl-record motif found on one section of Mitchell carpet, alluding to a topic, pop music, that has always fascinated the artist (in a former life she sung for floaty eighties indie band Talulah Gosh).

In formal terms, UNDERFOOT continues in the tradition typified by Price’s best-known work, ‘The Woolworth’s Choir of 1979’ (2012). That film spliced CAD-style projections of a church interior – accompanied by written expositions on architectural features and etymology – with footage of sixties girl band The Shangri Las and eye-witness accounts of a fire at a Manchester department store. Musical refrains swell, erupt, and fade. An interest in pop culture offsets a post-conceptual, information-led and archivistic bent. In particular, Price seems interested in how pop music might provide an emotional and ethical compass for navigating collective experience within modern society, in contrasting ways to institutional discourses weighed down by history and the prejudices of power.

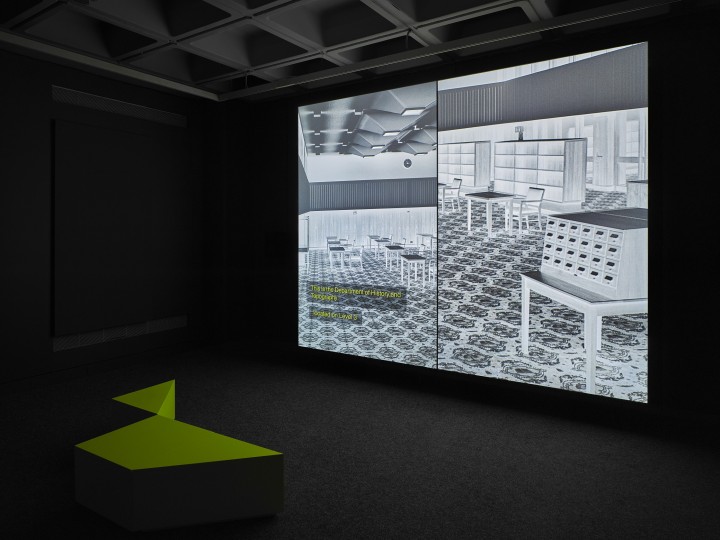

Installation of 'Elizabeth Price: Underfoot' at the Hunterian. Photo: Andrew Lee.

Installation of 'Elizabeth Price: Underfoot' at the Hunterian. Photo: Andrew Lee.

The present film takes us from room to room of the Mitchell using what seem like enlarged slide- negatives, with written accompaniments – as in ‘The Woolworths Choir’ – marked out by percussive clicks, in this case typewriter noises. These hint at the possibility of rhythm, of the film suddenly bursting into aural life, a possibility borne out in the jangly guitar refrain that marks the descriptions of the library’s carrels. These cell-like spaces for silent study can also be used for playing and practicing music. Their importance to Price is evident not only from the title of her rug-piece but also from the etymological dig that the film’s narrative then invites us on, finding connections to words such as carol and circle. Like the rivers of pattern underfoot, the carrels partly mark out a space for thought and expression as open-ended, joy-oriented rather than goal-oriented, in a world of divisions and labels.

The soundtrack – with its contrasts between sharp percussive sounds and sudden effluences of rhythm and melody – speaks to this same seesawing emotional and cognitive scope.

All of this seems to express an oblique position on social history, although, as with much of Price’s work, as much is obscured as is revealed. Do the techniques we use for storing collective knowledge miss something essential about the nature of human experience and expression? In what ways are those oversights classed and gendered? Archival photographs accompanying ‘SAD CARREL’ show women operating the machinery at Templeton and Stoddard, helping to establish the physical surroundings in which a generically masculine, middle-class form of knowledge is generated and upheld. At the same time, what of the connection to computers? In UNDERFOOT, carpet designs appear as luminous screens of enlarged pixels marking out gardens, hedgerows, wreaths, and flowers. We are shown and told about the rote mechanical processes used to bring them to life, “each spool set in sequence to roll out the image of a garden, abundant and empty.” There is no easy myth of untrammelled creativity presented in contrast to the A-Z enclopedism of the archive or referencing system.

The show seems, finally, to gesture towards the wider ramifications of the incipient era of computer technology, in which Stoddard and Templeton flourished. This was a time when questions such as the nature of human sentience in relation to the animal and mechanical, and how labour patterns and leisure time would be transformed by machines, were played out. What does our creativity mean, what does our work entail, and how will our stories be recorded now that human intelligence is circumscribed by the artificial? No answers, but a constellation of related questions, can be found amidst the empty, abundant gardens of the Mitchell Library’s carpets.

Elizabeth Price: UNDERFOOT is exhibited at The Hunterian until 16th April 2023.