Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Artist Spotlight: Joanne Coates

By Lena Kammerer, 26.08.2025

.jpg)

Red Herring, the result of visual artist Joanne Coates’ six-month residency at Timespan in the Highland village of Helmsdale, compellingly unravels the history of the Herring Girls: “an itinerant all-female workforce,” whose labour was vital to the British fishing industry from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. Anchored in this historical narrative, the exhibition invites broader reflection on the often-overlooked and multifaceted histories of women’s labour across time and space.

Coates, who is based in the North East of England and studied photography at the London College of Communication, describes the core concern of all her work to me as looking “at class in the countryside in really different ways”. This focus is often informed by her own lived experience as a working-class artist and farm labourer. Across various visual formats, her art engages with themes of rural life, marginalised histories of class and gender, and socioeconomic inequalities, frequently situated within broader environmental contexts.

“The project before this was about rural housing,” she explains. “It was called The Middle of Somewhere (2024), and it is looking at the issues around housing in the UK, but in the context of rural places and spaces and also that new gentrification of those areas. The fact that those working-class communities in those areas are being pushed away and they’re not able to stay, but those areas are accessible for anyone.”

Her fascination with the fishing industry, conversations about which eventually led her to the Herring Girls, fully emerged during her foundation year when her first arts project focused on “smaller-scale fishermen”. In North Sea Swells (2012–2019), a continuation of her early work, she captured the rhythms and realities of the fishing industry through her camera, documenting the lives of local communities across Scotland’s Highlands and Islands over a five-year period.

Being also particularly interested in “different forms of women’s work,” reflected in her photographic series Daughters of the Soil (2021), which explores the role of gender in agriculture within communities in Northumberland and the Scottish Borders, Coates was intrigued by the stories of the Herring Girls - women who travelled seasonally between coastal towns to gut and pack fish brought ashore, physically demanding work often performed under harsh conditions.

Archival research for Red Herring, 'Herring Girls Shetland'. Image courtesy of Getty and Timespan

Archival research for Red Herring, 'Herring Girls Shetland'. Image courtesy of Getty and Timespan

However, the statues commemorating these “Fisher Lassies” often “felt quite removed” to her. “It didn’t tell me anything about the labour or their kind of history or the fact that they were migratory workers.” A 2012 visit to the Wick Heritage Museum cemented Coates’s curiosity about the history of these female labourers. “That was the first time that I really was like: I want to do something about this.”

During Coates’s initial discussions with Timespan, the topic of the Herring Girls resurfaced. Helmsdale had not only been shaped by the Highland Clearances but was also deeply implicated in the transatlantic herring trade. Coates subsequently embarked on months-long research, characteristic of her work, that combined community collaboration with researching in archives, aiming to piece together a more comprehensive history of these rural working-class women’s lives and labour.

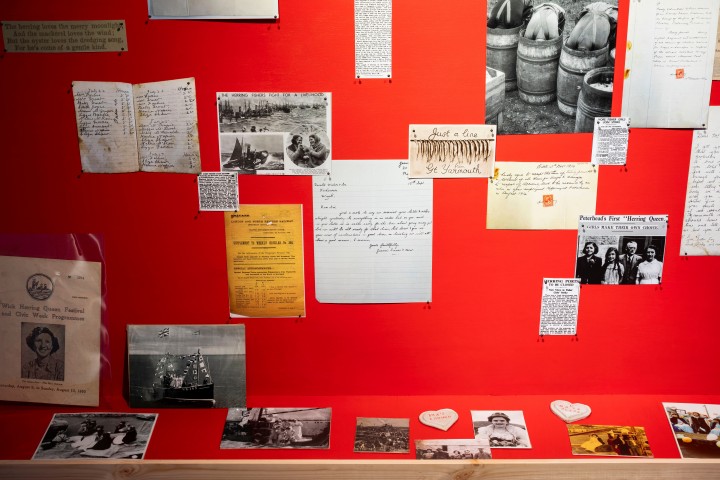

Red Herring exhibition install image, courtesy of Timespan

Red Herring exhibition install image, courtesy of Timespan

Reflecting on working with the local community, an essential and recurring feature of her wider practice that she deems indispensable to her work, she recounts, “There wasn’t many people in actual Helmsdale who had been Herring Girls left. It was these kinds of broken-down memories; post-memory-like visitations of what happened. Like stepping into a bucket of cold water or hot water to keep your feet warm, and how cold it was, and the harsh conditions.”

.jpg) Red Herring exhibition install image, courtesy of Timespan

Red Herring exhibition install image, courtesy of Timespan

A central component of the exhibition evokes this sensory, fleeting memory of the Herring Girls’ lived realities through reenacting these remembered scenes, thereby subverting the gaze of those historical photographs that portrayed the gendered notion of a passive, acquiescent rural working-class woman. A series of six black-and-white photographs shows Coates, visible only from the waist down and dressed in a long black dress, stepping in and out of a bucket.

This performance holds particular significance, she tells me. “The performative work stuck with me because I’d started doing performative work to talk about my own situation of class and disability.” Her practice often spans various media, including installations and audio works, but she still sees photography as her foundation: “Photography is really key to everything.” At the same time, she enjoys “pushing the medium and experimenting with different things and bringing all of that in and together” to fully capture the complexity of her subjects. “It’s almost like the medium is the message.”

The photographs, assembled alongside other objects created by Coates such as ceramics and blood-red-tinted vinyl curtains reminiscent, albeit not in colour, of those in fish factories, not only evoke the post-memory of overlooked female labour but also, as Coates explains, are intended to draw references to the present moment, where women’s rights are increasingly under threat.

The temporal layering of past and present has been further deepened through her extensive research, which draws on a plethora of archival documents, including from the Timespan archives, the Shetland Museum and Archives, and the North Carolina State Archives. Coates asked herself: “How can going back to an archive, how can looking at a story, retelling the story - how can that make us think about what’s happening in the present? For me, it’s that activation.”

Through incorporating parts of these materials into the exhibition, Coates explores broader themes inextricably tied to the histories of the Herring Girls, including the global and contemporary dimension of this seemingly local labour history, geographically reaching as far as North Carolina and temporarily alluding to today’s gendered labour in the fishing industry and beyond, uncovering the herring industry’s links to wider systems of colonialism and labour extraction.

Coates powerfully utilises her socially-engaged visual art practice, in its various forms, to reexamine and challenge the pervasive narratives surrounding social and economic power and identity. The story of the Herring Girls as a historical instance of overlooked women’s work poignantly alerts us to the ongoing concerns about the gendered nature of labour and its past and present representation.

“I’m so interested in the gaze and how people are represented. How especially working-class people are represented and the negative stereotypes around them. I think it’s really important to bring the community in in different ways, because otherwise, even though I have lived experience, I don’t have lived experience of a Highlands woman. I have the experience of like an English working-class rural woman, and so having those discussions where you’re also questioning your own ideas are really important.”

Red Herring is exhibited at Timespan, Helmsdale until 30 September 2025