Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

A State of Mind

By Susan Mansfield, 17.12.2025

When Reinhard Behrens found a toy submarine on a beach in North Frisia, Germany, in 1974, he could not have imagined the significance it would come to have in his work. Then an art student in his home city of Hamburg, he simply added the brightly coloured gadget to his collection of beachcombing finds.

The following summer, while he was on the Aegean coast of Turkey working as an artist for the German Archaeological Institute, he picked up a Turkish newspaper. Unfamiliar with the language and woozy from sunstroke, he could read only one word, the name of a cargo ship which had been involved in an accident with a submarine: Naboland.

“That reminded me, in that feverish moment, of the submarine I had found a year earlier, and I thought maybe if I ever make it back to Hamburg, that’s what I could try out as an artist. I could travel, explore parts of Naboland, it sounds like a fantastic country.”

Fast forward five decades to a solo exhibition at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh in October, celebrating 50 Years of Naboland, the imagined world which has provided the context for his life’s work. The little submarine has pride of place in a glass case next to a framed letter he received from a Government department during the Brexit roll-out addressed to ‘Expeditions to Naboland’. “It’s such a precious thing to me, because a feverish idea 50 years ago in Turkey has led to living in Scotland, and the British state even recognises Naboland in its official correspondence!”

He came to Scotland in 1979 as a postgraduate to spend a year at Edinburgh College of Art, fell in love with the country, and with Margaret Smyth, his future wife, also an artist, and never went back.

I meet Reinhard and Margaret in their family home in Pittenweem which they open every summer during the Pittenweem Arts Festival to show off the work of the whole family: daughter Kirstie is a graduate of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design and a talented printmaker, son David is a musician and composer but also a maker of fine kinetic sculptures and automata. When Christina Jansen, director of the Scottish Gallery, came to visit, she signed up the whole family to take part in the show.

We drink tea in the cosy sitting room with its views of the sea among Margaret’s paintings and David’s collection of musical instruments and talk about Naboland. Reinhard speaks softly and seriously, with a hint of German intonation; after nearly five decades in Scotland, he is a master of deadpan humour. Margaret reflects, clarifies. Their sentences weave around one another.“It’s a magical country, it’s a parallel world, these probably apply,” he says, thoughtfully.

Reinhard Behrens, 'Acqua Alta, Canale Grande', image courtesy of the artist

Reinhard Behrens, 'Acqua Alta, Canale Grande', image courtesy of the artist

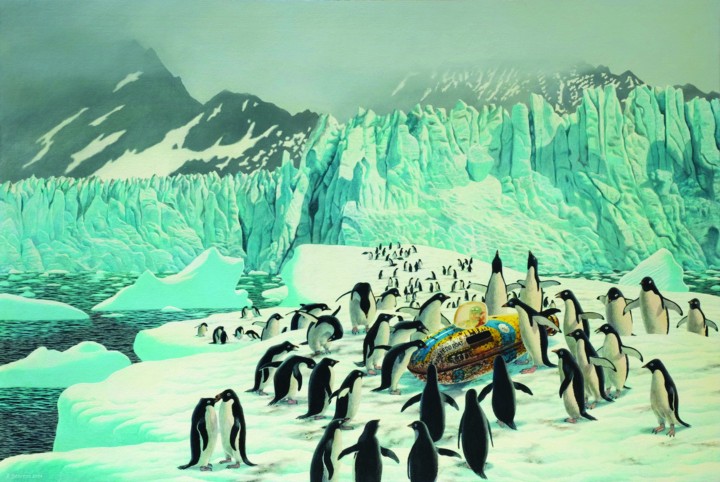

The submarine is its signature. In his paintings, it visits polar wastes, is towed by camel trains across empty deserts, is strapped to the back of a yak in the Himalayas or moored in a wintry Venetian canal. In recent work, it has visit Scottish landmarks such Callanish, Glencoe, Skara Brae. It’s our world, but not quite our world.“Just because it’s a toy, people have suggested it would make a marvellous children’s book,” he says. “Yeah, maybe it would, but I try to be a serious artist, so it should be more than that. It’s probably less a possible geographical space, it’s more a kind of state of mind.”

There’s often an element of fun, though, or playfulness. “I think [humour] is one of the oxygens to keep me going. And the humorous element allows me to make serious points.”

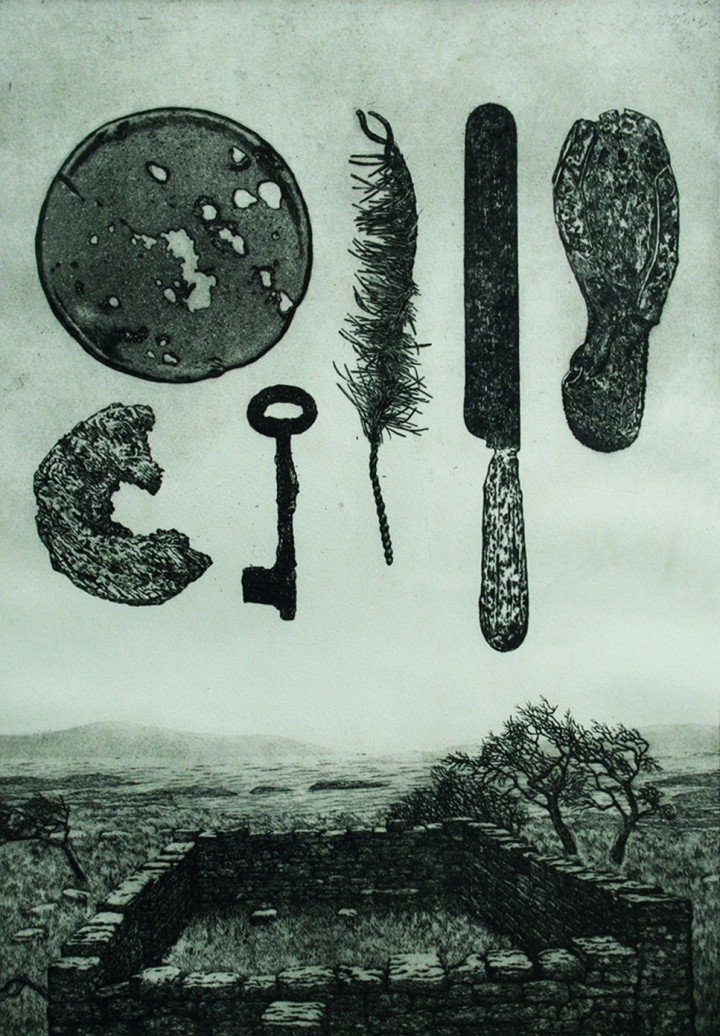

Following a trip to Nepal in 1990, he created a show called The Last Yeti in the Barrack Street Museum in Dundee, which also held the city’s natural history collection. Visitors went from seeing dinosaur bones to Reinhard’s casts of yeti footprints, unsure what was real and what was imagined. “I sometimes feel bad because people are obviously willing to learn, how easy it is to deceive them in a friendly way.”He is still a collector, a beachcomber, often drawing his finds in gorgeous detail to make works like ‘Boreraig, Skye’ (1986), which was recently purchased for the Fleming Collection.

It’s as if the little pilot of the submarine were trying to make sense of the strange world in which he has landed. “I think the power is in the subtlety,” Margaret says. “It’s shining a light on a situation which is then reflected back at you, and so you see it slightly differently.”

Scotland, Reinhard says, gave him fertile ground in which Naboland could flourish. His early work was supported and encouraged, with exhibitions of his life-size installations at venues like Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Gallery. “I don’t think the notion of Naboland would have run very long in Germany because there’s not that tradition of tongue-in-cheek humour, playing with ‘what if’, with different levels of reality, that’s what I remember from my training. There wouldn’t have been that desire to laugh about art.” However, he recognises that the significance of the work has shifted. What felt like a spirit of exploration in the late 1970s now can’t ignore the reality of climate change. “I started out being fascinated by the Arctic and Antarctic, these beautiful worlds of ice, the stories of Scott and Shackleton, thinking it’s there forever, it’s eternal landscape. And now we know it’s so threatened. I can’t afford to be innocently enjoying those worlds without being aware of that threat.

“When I was first beachcombing, I discovered the richness and the randomness with which things are washed ashore. Now we can’t help but all be taken by the excess of plastic materials. Genuinely, there are more reasons to worry nowadays than there were 50 years ago.”

Reinhard Behrens, 'Trip of a Lifetime', courtesy of the artist and The Scottish Gallery

Reinhard Behrens, 'Trip of a Lifetime', courtesy of the artist and The Scottish Gallery

The shift is there in the titles. The painting of the submarine among the penguins is called ‘Trip of a Lifetime’, one of the Venice paintings is called ‘High Water’ (‘Acqua Alta’) to reflect rising sea levels rising. “The submarine is a metaphor for us humans in the natural environment, blundering around, or just being bystanders. That’s what I feel on a more serious level, do humans treat nature as a resource that can be plundered, or realise that we are part of nature?”

Having retired from teaching at Duncan of Jordanstone, he is glad to have more time to spend on his work, and much of the Scottish Gallery show was made in the last two or three years, each meticulous piece surely representing many hours of labour. “If artists were to take that tricky path of working out what their hourly rate is, people would just freeze and say ‘Okay, I should have become a dentist!’” he chuckles.

“So there must be something in all of us artists that keeps us going beyond that. It’s because we do something that we would do for free anyway. If it wasn’t for the basic enthusiasm, I would probably have given up long ago.”

“In some ways, I still feel like I’ve just left art college in Hamburg and there’s a whole world ahead, and I can do my art. That’s the thing that can’t be bought for money. In the end it’s 50 years of Naboland, and it’s 50 years of just keeping going as an artist.”