Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

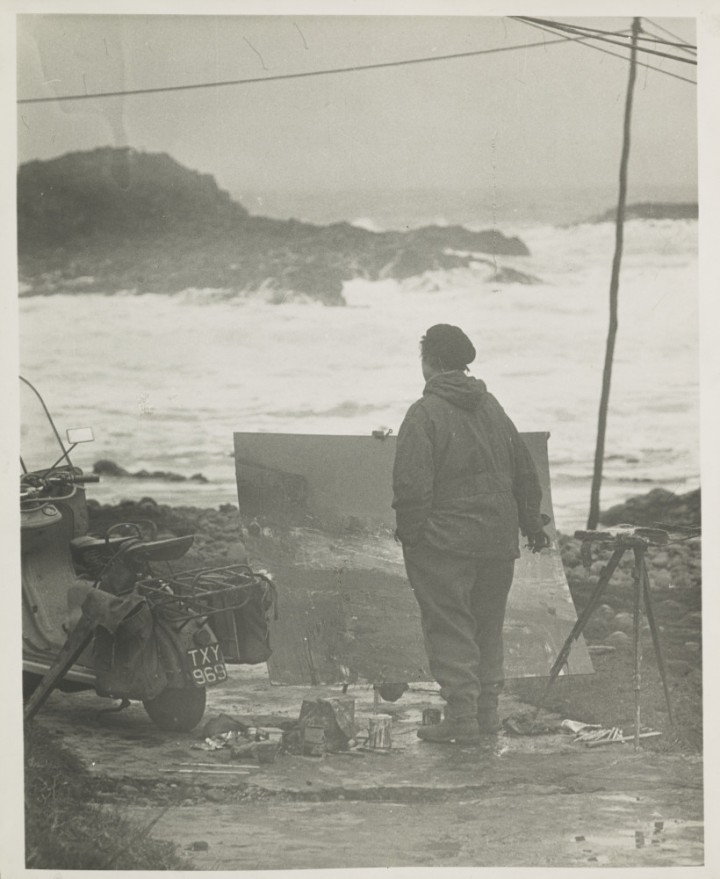

A Life in Catterline

By Patrick Elliott, 15.11.2021

Five years ago, we staged the show Joan Eardley: A Sense of Place at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. It focused on the work Eardley did in the Townhead area of Glasgow, among the crumbling, overcrowded Victorian tenements, and in Catterline, the tiny fishing village on the north-east coast, where she made her home.

The Glasgow work focuses on the poor children who scampered about her studio and became her favourite subjects, while the Catterline pictures are almost devoid of human presence. Yet there was a strong connection between the two places. They were both tight-knit communities confronting an uncertain future. Townhead faced the developer’s wrecking ball and a 1960s motorway interchange. In Catterline, the young had left and many of the little cottages were uninhabited with no mains water or electricity.

When you organise a show, you always come across information when it’s too late. I met Ron Stephen by chance, not long before our show opened. He was in the audience of a play about Eardley and politely pointed out that a few things weren’t quite right. Everyone turned round. He knew because he had been there. He and his dad had collected Eardley from Stonehaven train station when she first came to stay in the village in 1952.

Fishing-nets Hung up, Joan Eardley. Presented by the artist's sister, Mrs P.M. Black, 1987 © Estate of Joan Eardley.

Fishing-nets Hung up, Joan Eardley. Presented by the artist's sister, Mrs P.M. Black, 1987 © Estate of Joan Eardley.

I went up to Catterline a couple of times with Ron. He could point to the exact spots where Eardley had painted many of her pictures and could tell, by the position of the sun, what time of day it must have been, or by the position of the boats and the nets, what season it was. This was gold, but in order to balance the Glasgow and Catterline narratives in the show and catalogue, we had to leave much of this information aside. We’ve exchanged hundreds of emails and phone calls since.

The idea of publishing a book specifically on Eardley and Catterline, to coincide with Eardley’s centenary in May 2021, emerged at that time.

While A Sense of Place was on display, we had some lucky breaks. I met Jonathan Stansfeld, who had run the salmon fishing industry along that stretch of the east coast from the late 1950s onwards. Salmon fishing was central to the economy of the village. The nets you see in Eardley’s Catterline paintings are salmon nets, but one looks at them almost as compositional devices. Mr Stansfeld explained everything you could want to know about salmon and more: if a painting shows the nets hanging up on poles, for example, it has to have been painted at the weekend, between February and August.

Many of the people in Catterline came forward to talk about Eardley. A neighbour remembered her painting in winter at the foot of her garden in 1963. Another recalled the visits of the baker, milk and grocery vans and how Eardley lined up with everyone else but was too shy to speak. Mr Simpson, the first headmaster of the local school which opened in 1956, is still going strong at 100. Although the village was tiny and he lived only a few houses away from Eardley, he was apologetic that he had never had a proper conversation with her. That in fact said everything. Eardley liked Catterline because nobody bothered her there. She was lesbian, but they either didn’t know or didn’t care. Everyone was polite but she could get on with her life. The Glasgow art world in the 1950s was a tough, hard-drinking, macho place. No wonder the windswept beach at Catterline appealed.

Outside No 18 Catterline. Joan Eardley sitting on bench outside cottage. Photographer and date unknown. From the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art archive.

Outside No 18 Catterline. Joan Eardley sitting on bench outside cottage. Photographer and date unknown. From the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art archive.

Several people came forward with letters and memories. Most important of all was a box of unpublished letters exchanged between Eardley and the artist Lil Neilson, who met and became lovers in autumn 1962. With Neilson living in England, the letters focus on day-to-day life. Eardley’s neighbour, Mrs Taylor, looms large. A marvellous figure, straight out of a Balzac novel, she wore light summer dresses all year round, cleaned the church, cooked dinner at the school, kept a goat, delivered newspapers and often popped by with food for Eardley. In turn, Eardley collected her pension from the Post Office on the main road and got her a bucket of water every day from the spring tap at the foot of the brae. The artist Angus Neil, who followed Eardley to Catterline and did odd-jobs for her, is also ever present.

Eardley speaks of the books she read (often high-brow: Proust, Beckett, Sartre), her desperation to learn to drive, and her love of music (Ella Fitzgerald was ‘fabulous’), which she first listened to on a wind-up gramophone. When she moved to a cottage with electricity, she bought a television. She was only the second person in the village to have one. It was mainly so that a friend could watch Wimbledon but we find Eardley watching it occasionally, enjoying the up-market arts programme Monitor, but also reveling in Diana Dors’ appearance on Juke Box Jury.

Eardley emerges as both ordinary and extraordinary. You can see that the village, and the villagers, were vital to her development as an artist.

Patrick Elliott is Chief Curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. He has written extensively on modern and contemporary art. Joan Eardley: Land & Sea – A Life in Catterline is available to order National Galleries Scotland.