Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Scottish Modernism in Venice

By Bill Hare, 01.05.2017

When the phrase ‘Scottish Art, Home and Abroad’ comes up, Venice does not usually spring to mind. Rather it is other great cities of culture, Rome or Paris perhaps, that more readily fit the bill. In the 18th century for instance, the Scottish aristocratic traveller looked mainly on Venice as pleasurable, and in many cases as an erotic diversion. It was in the Eternal City that the high cultural desires and needs of the Grand Tourist were fulfilled. To meet such demanding aspirations, there was a whole colony of eager young Scots artists on call in Rome, where the all-powerful Gavin Hamilton was at the centre of an international network of artistic promotion and patronage.

Later, in the 19th and 20th centuries, it was Paris that took over as the major artistic attraction for young aspiring Scottish artists. A whole generation, from William Gillies to Jack Knox, attended André Lhote’s Parisian studio academy throughout the first half of the 20th century. In order to draw the attention of the wider world back to the city, Venice established the first Biennale in 1895 and, since then, its reputation has grown immensely throughout the international art scene. It is not surprising, then, that Venice was very determined to re-instate as quickly as possible its hard-won artistic and curatorial status after the hiatus of the Second World War. This it succeeded in doing by 1948, and over the next decade or so, the Venice Biennale became an important launching stage for the international careers of three Scottish modern artists – Alan Davie (1920–2014), Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005) and William Turnbull (1922–2012).

Alan Davie attended Edinburgh College of Art and was awarded his diploma in 1940. After his war service, he was unsure what direction his creative life would take; whether it would be poetic, artistic or musical. In 1948 however, an Andrew Grant travelling scholarship allowed him, and his new wife and constant companion Bili, to visit the great art centres of Europe. This richly rewarding experience was to have a profound and lasting effect on Davie.

In April 1948, Davie set off on his own personal grand tour of European culture in a very defiant and iconoclastic frame of mind as seen from his letters and journal of the time: of the art scene in London, he dismissively wrote, ‘that which I am seeking is not here . . . what a mass of ugly rubbish on show under the name of Art.’

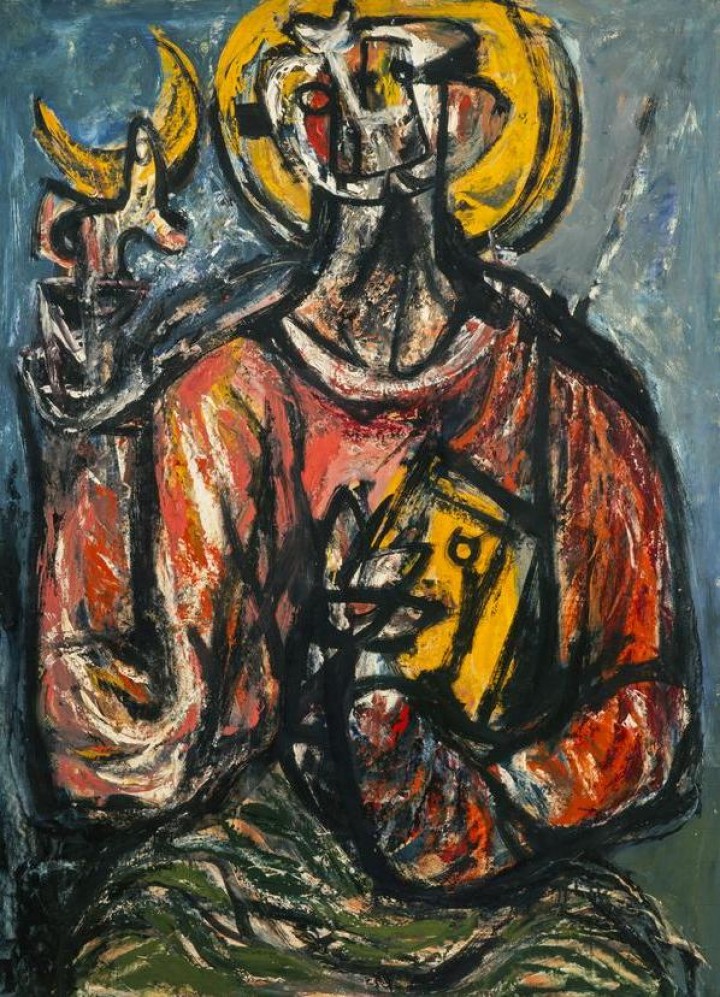

When Davie got to Italy he was equally unimpressed by Renaissance and Baroque art and architecture. Writing of St Peter’s in Rome, he declared, ‘words cannot express my horror on seeing this wonder of the world. I can only say that it is the most hideous of monstrosities ever thrown up by mankind.’ To find the inspiration he was desperately seeking, Davie needed to seek out a different kind of art, and it was in Venice (and later in Sicily) that he found it in the form of mosaic religious icons. For Davie, such works were not sullied by the insidious fakeries of Albertian pictorial illusionism. These early Christian images were instead created through the open display and flat patterning of the mosaic medium, where form and background were as one, holding the holy imagery within an ‘eternal vision’. Davie’s inspired response to such visual mysticism can be seen in such powerful work as his radiant The Saint (1948).

William Turnbull, Heavy Insect, 1949 © the estate of William Turnbull. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Photo credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art.

William Turnbull, Heavy Insect, 1949 © the estate of William Turnbull. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Photo credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art.

Davie’s visit to Venice coincided with the Biennale of 1948 where, through the auspices of the great American patron Peggy Guggenheim, he had his first opportunity to see recent American painting, including the work of Jackson Pollock. The Biennale’s wide-ranging display of modern art was so mesmerising for the young Scottish painter that, according to his journals, he visited it seven times and wrote, ‘at last I can say that my whole life is completely absorbed in art and painting.’ This outburst of creative activity resulted in his first exhibition in Florence in September and another in Venice at the Galeria Sandri in late 1948.

The Venice show drew the attention of none other than Peggy Guggenheim herself. She initially thought this was the work of an unknown American painter, and was so impressed that she purchased one work, Music of the Autumn Landscape (1948) for her peerless collection of 20th century art. Even more of a boost for Davie’s burgeoning career was her recommendation to seek out a highly regarded London gallery, which resulted in the first of his many exhibitions at Gimpil Fils in September 1950.

Through the Guggenheim connection, Davie later visited the USA in 1956 where he met up with most of the major abstract expressionists and also had his first American exhibition at Catherine Viviano Gallery, from which MOMA purchased Magic Box (1955). As an homage and token of his gratitude he felt towards his first patron, Davie entitled one of his most important early works Peggy’s Guessing Box (1950--2).

Like Alan Davie, when Eduardo Paolozzi and William Turnbull finished their war service and set out on their post-war artistic careers, they were similarly disappointed with the art scene in Britain. In an interview for Scottish Art News in 2013, Turnbull said, ‘When I got de-mobbed I enrolled at the Slade. It was one of the biggest let-downs I had experienced. So I went to Paris because I wasn’t interested in the artists in London, I was interested in the artists in Paris.’ There in the late 1940s, he shared a studio with Paolozzi and both had access to meeting and seeing the work of the great modern sculptors such as Brancusi, Giacometti and Dubuffet. The direct contact with these most renowned exponents of modern sculpture had an encouraging effect on the early experimental work of the young Scottish artists.

When Paolozzi and Turnbull returned to London in 1950, they immediately sought out a circle of progressive artists and patrons, this time linked to the ICA (Insitute of Contemporary Arts), which had been set up by Peggy Guggenheim, Roland Penrose and Herbert Read as a centre for progressive and experimental art and ideas.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Fountain, 1951-51. © Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2021. Photo credit: Tate

Eduardo Paolozzi, Fountain, 1951-51. © Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2021. Photo credit: Tate

Immersing themselves in the British art scenes bore fruit, particularly for Paolozzi, who was commissioned for the prestigious Festival of Britain to make his first large public sculpture entitled Fountain (1951). It also took Paolozzi and Turnbull to Venice, where they were included among a group of new generation sculptors chosen to represent Great Britain at the Venice Biennale of 1952. This was the famous exhibition ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’ selected by Herbert Read. For the exhibition catalogue, Read wrote his controversial ‘Geometry of Fear’ essay, implying that this group of young British sculptors were a homogenous movement; all committed to an ‘iconography of despair’ -- which most of them certainly were not. It should also be pointed out that the philistinism which Davie and Turnbull noted after the war was still very much a dominant force in British society, as shown by the Guardian’s art critic who questioned ‘why are we sending to Venice the bronze biscuits and plaster pies by William Turnbull and Eduardo Paolozzi?’

The reaction of the international art scene in Venice was very different. Alfred Barr, renowned director of MOMA, declared it the most powerful display of modern sculpture on show and purchased four works, including one by Paolozzi. Like Davie, Paolozzi also caught the attention of Peggy Guggenheim. The recognition the artists received from powerful figures in the international art world was quickly followed by the support of the British Council, which went on to sponsor younger emerging artists like Turnbull and Paolozzi by buying their work for its collection and also regularly including them in its worldwide touring exhibitions.

When Turnbull exhibited in the 1952 Biennale, he was ‘completely broke and working the night shift at a Lyons Maid ice-cream factory and couldn’t afford to go to Venice.’ Following the success of the show, he was soon offered a teaching position by fellow Scot William Johnstone, principal at the Central School of Art in London. He then also became, along with Paolozzi, a leading member of the newly formed, and soon to become highly influential, ‘Independent Group’ at the ICA, as well as a regular exhibitor with the Waddington Gallery.

It was the charismatic Paolozzi, however, who benefitted the most from British Council patronage, resulting in him having the whole of their sculpture pavilion at the Venice Biennale of 1960. This gave him an important opportunity to present a carefully selected group of his 1950s Art Brut figures, including his forbidding His Majesty the Wheel (1958) and Krokadeel (1956). This won him the Bright Foundation Award for the best sculptor under 45. Even more significant for his subsequent career, Paolozzi met Gabrielle Keiller in Venice. She quickly became his most important patron and collector, and could have on occasions more than 75 Paolozzi sculptures on display in her extensive garden at Kingston Hill, London.

Bill Hare is an Honorary Fellow at The University of Edinburgh, as well as a freelance writer and curator